The Landscape Architect's Process: Schematic Design

A great landscape design doesn’t just happen: it’s the result of a process. Building on our previous post about the Pre-Design phase, this is the second in a series of six posts describing our process:

The Schematic Design Phase

While some landscape architects consider Schematic Design a sub-phase within the “Preliminary Design” phase (more on that later), we think Schematic Design stands on its own for any plan that comprises outdoor rooms and the circulation among them.

The Schematic Design phase (which we call “SD” in our workflow) is all about exploration and discovery. It’s the dreamer of the process, the idealist. Its purpose is to find the optimal relationships between various spaces in the landscape, as well as between the landscape and the existing home or environment. It’s a treasure hunt, a jigsaw puzzle, and a magical mystery tour all in one.

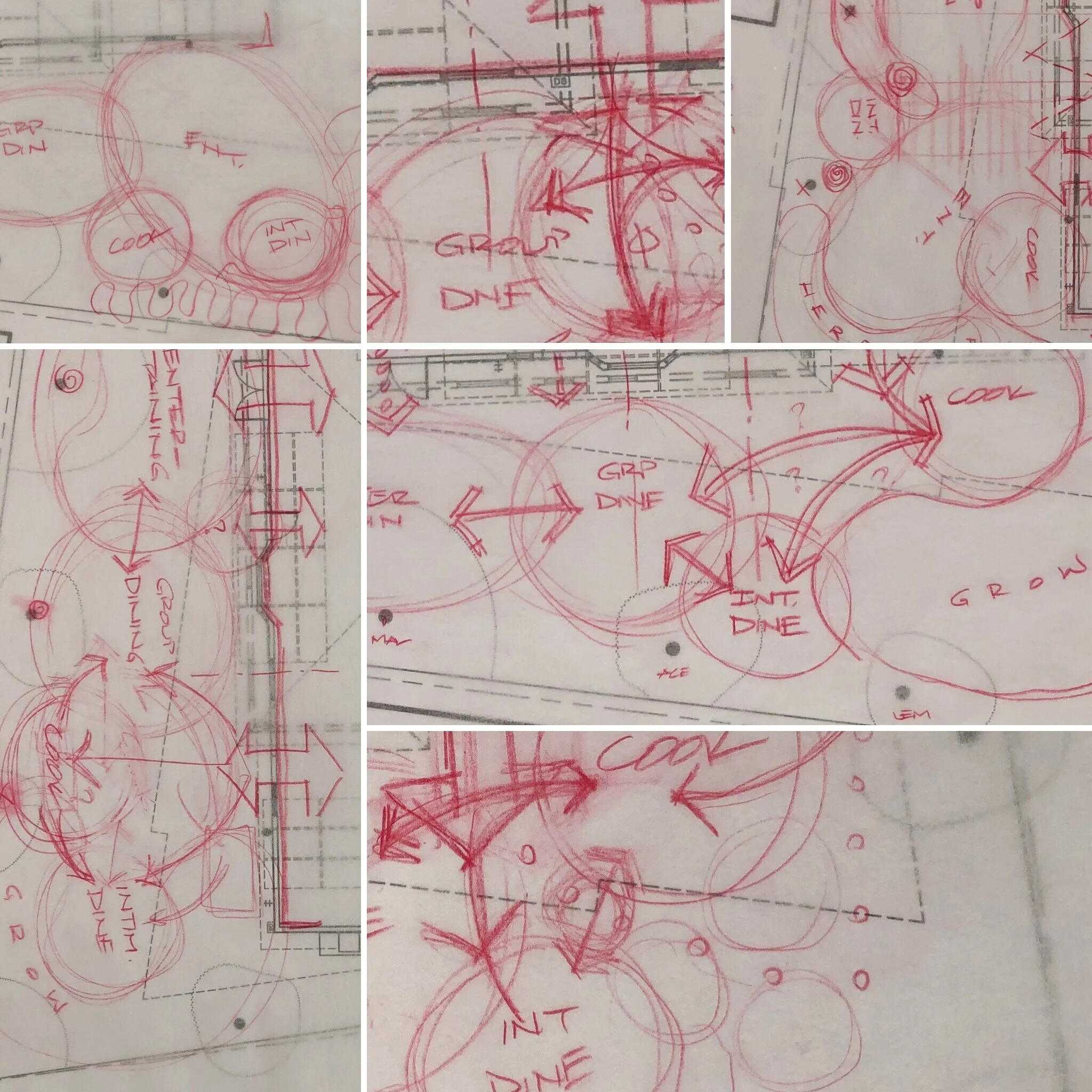

Because it’s focused on how the spaces in the landscape will be used, not so much what they look like, different landscape designers call this phase different names: Functional Diagrams, Spatial Relationships, Design Concepts, or Bubble Diagrams, for the loose circles we quickly sketch to indicate the general location of each function on the site.

To confuse things further, the architecture industry often still uses “schematic design” to describe buildings whose dimensions and forms are really quite well defined, not just the spatial relationships of their rooms and functions. We, however, maintain that those are well beyond the true SD phase—because the very definition of “schematic diagram” is a simplified, abstract graphic representation of the elements of a system. One of the best schematic diagrams we’ve ever seen is the map of the London subway system.

We begin Schematic Design with four things in hand:

The list of functional (not so much aesthetic) wishes and needs from our design program;

The base map and site analysis created during our Pre-Design phase;

A red pencil (we use Prismacolor Carmine Red); and

Tracing paper. Lots of tracing paper.

The Schematic Design phase aims to generate as many ideas as possible, in order to find a unique and elegant solution.

Then we start reconciling (1) with (2): Should the outdoor dining room be in the sun or the shade? Is this area too breezy for the swimming pool? How should the outdoor kitchen relate to the indoor kitchen? Where’s the best sunny spot for the rose garden to be viewed from indoors? There are a lot of what-ifs explored, and a lot of false starts. Our goal is to generate as many ideas, even bad ones, as possible. Tracing paper is cheap.

Sometimes the solutions are obvious: a classical design probably wants the pool to be on-axis with the lines of the home. Often, though, the obvious solution actually isn’t the best one; so even if we think we’ve found The Answer, we keep going. Persistence leads to serendipity. “Good enough” isn’t. We may develop a dozen concepts in hopes of yielding two viable options. The process is a mental sprint, so we tend to work in relatively short bursts — maybe an hour at a time, maybe twice a day, over maybe a week. Diminishing returns tell us it’s time to set down the pencil and turn to something else for a while, to allow the creative reserves to replenish.

How do we decide which concepts to present to the client? We return to the design program, and ask which of our newborn concepts solve our needs most elegantly, most originally, and most efficiently. Ideally we will present four or fewer; more than that, and it’s pretty certain we won’t be showing the best of the best. Our guiding question is, “would we be delighted if the client chose this one?”

Usually, the first schematic designs we present are close but not perfect. And that’s perfect. Because SD isn’t meant to be the end of the creative conversation, but the beginning. We want our clients to respond. We want them to be inspired, and engaged. We want their brains to start whirring a bit, just as ours have been. Their reactions get fed back into our process, and we’ll revise the concepts, until we all feel great about the road map we’ve created. Then, and only then, it’s on to the Preliminary Design phase.